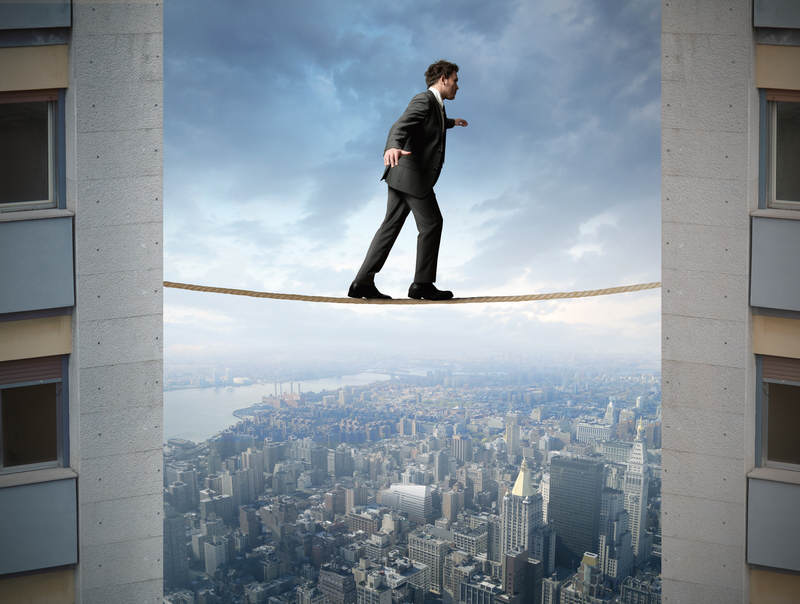

Employees’ willingness and ability to stop unsafe operations is one of the most critical parts of any safety management system, and here’s why: Safety managers cannot be everywhere at once. They cannot write rules for every possible situation. They cannot engineer the environment to remove every possible risk, and when the big events occur, it is usually because of a complex and unexpected interaction of many different elements in the work environment. In many cases, employees working at the front line are not only the first line of defense, they are quite possibly the most important line of defense against these emergent hazards. Our 2010 study of safety interventions found that employees intervene in only about 39% of the unsafe operations that they recognize while at work. In other words, employees’ silence is a critical gap in safety management systems, and it is a gap that needs to be honestly explored and resolved.

An initial effort to resolve this problem - Stop Work Authority - has been beneficial, but it is insufficient. In fact, 97% of the people who participated in the 2010 study said that their company has given them the authority to stop unsafe operations. Stop Work Authority’s value is in assuring employees that they will not be formally punished for insubordination or slowing productivity. While fear of formal retaliation inhibits intervention, there are other, perhaps more significant forces that keep people silent.

Some might assume that the real issue is that employees lack sufficient motivation to speak up. This belief is unfortunately common among leadership, represented in a common refrain - “We communicated that it is their responsibility to intervene in unsafe operations; but they still don’t do it. They just don’t take it seriously.” Contrary to this common belief, we have spoken one-on-one with thousands of frontline employees and nearly all of them, regardless of industry, culture, age or other demographic category, genuinely believe that they have the fundamental, moral responsibility to watch out for and help to protect their coworkers. Employees’ silence is not simply a matter of poor motivation.

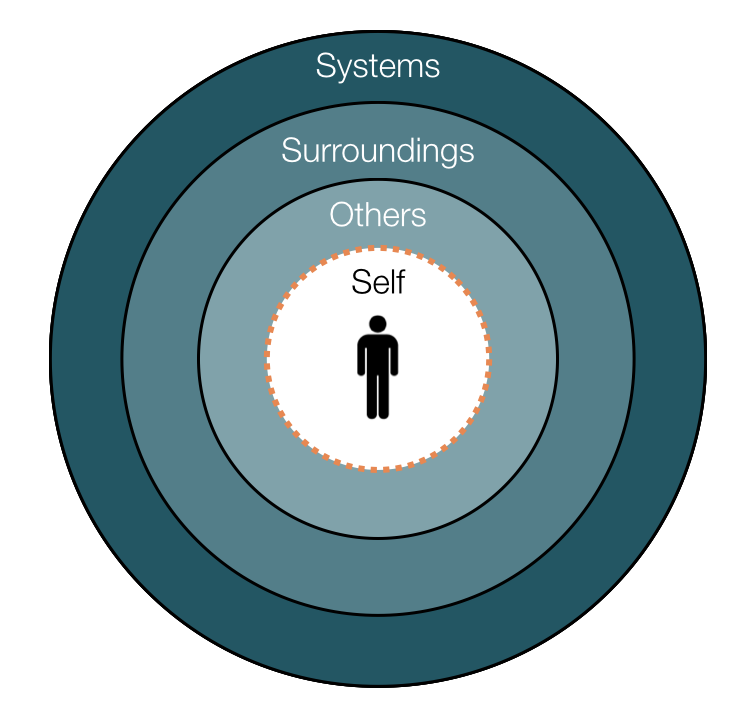

At the heart this issue is the “context effect.” What employees think about, remember and care about at any given moment is heavily influenced by the specific context in which they find themselves. People literally see the world differently from one moment to the next as a result of the social, physical, mental and emotional factors that are most salient at the time. The key question becomes, “What factors in employees’ production contexts play the most significant role in inhibiting intervention?” While there are many, and they vary from one company to the next, I would like to introduce four common factors in employees’ production contexts:

THE UNIT BIAS

Think about a time when you were focused on something and realized that you should stop to deal with a different, more significant problem, but decided to stick with the original task anyway? That is the unit bias. It is a distortion in the way we view reality. In the moment, we perceive that completing the task at hand is more important than it really is, and so we end up putting off things that, outside of the moment, we would recognize as far more important. Now imagine that an employee is focused on a task and sees a coworker doing something unsafe. “I’ll get to it in a minute,” he thinks to himself.

BYSTANDER EFFECT

This is a a well documented phenomenon, whereby we are much less likely to intervene or help others when we are in a group. In fact, the more people there are, the less likely we are to be the ones who speak up.

DEFERENCE TO AUTHORITY

When we are around people with more authority than us, we are much less likely to be the ones who take initiative to deal with a safety issue. We refrain from doing what we believe we should, because we subtly perceive such action to be the responsibility of the “leader.” It is a deeply-embedded and often non-conscious aversion to insubordination: When a non-routine decision needs to be made, it is to be made by the person with the highest position power.

PRODUCTION PRESSURE

When we are under pressure to produce something in a limited amount of time, it does more than make us feel rushed. It literally changes the way we perceive our own surroundings. Things that might otherwise be perceived as risks that need to be stopped are either not noticed at all or are perceived as insignificant compared to the importance of getting things done. In addition to these four, there are other forces in employees’ production contexts that inhibit them when they should speak up. If we're are going to get people to speak up more often, we need to move beyond “Stop Work Authority” and get over the assumption that motivating them will be enough. We need to help employees understand what is inhibiting them in the moment, and then give them the skills to overcome these inhibitors so that they can do what they already believe is right - speak up to keep people safe.