In one way or another, culture helps to shape nearly everything that happens in and around an organization. As important as it is, though, it can be equally as confusing and hard to control. Work cultures seem to emerge as an unexpected by-product of randomness — a brief comment made by a manager, misinterpreted by direct-reports, propagated during water cooler conversations, and exaggerated by unrelated management decisions to downsize, reassign, promote, terminate, etc.

Using Human Factors to Survive, and Even Thrive, in an Economic Downturn

As we are all aware the oil and gas industry is currently deeply entrenched in a global downturn rooted in an enormous glut of oversupplied crude. It seems that each and every day we hear a different expert give their analysis of when this downturn will end and prices will rise but the consistent message is that we will not see rising crude prices until we can start burning a lot more than we produce, and for an extended period. While we at The RAD Group don’t participate in the speculation of crude prices, we certainly understand the impact that a weak sector can have on profits, morale, and just about every other KPI that companies measure. You may not be directly effected by this current downturn but you’ve probably been through one in your own industry or will at some time in your career. As you may also be aware as one of our readers, we do focus on the application of Human Factors science to improve the performance of individuals, teams, and entire organizations. To this end, let’s take a look at how organizations could use Human Factors principles to survive, and even thrive, in a market downturn.

What in the World Were They Thinking?

As I write this, the Houston area is dealing with the aftermath of a 500-year flood that has left several feet of water in areas that have never flooded before. Some areas received 15- to 20-inches of rain in less that 6-hours which left all of the creeks and bayou’s overflowing their banks and inundating residential areas, displacing several thousand people and shutting down travel in much of the area. As I watched live television coverage of this event from my non-flooded home I was saddened by the impact on the lives of so many, but initially struck by the “stupidity” of those who made decisions that put their lives at risk and in a few cases cost them their lives. I began to try to make sense of why these individuals would make what appeared to be such fool-hearty decisions. What could they have been thinking when they drove past a vehicle with flashing lights right into an underpass with 20 feet of water in it? What could they have been thinking when three people launched their small flat-bottom, aluminum boat to take a “sight-seeing” trip down a creek that was overflowing with rushing waters and perilous undercurrents only to capsize, resulting in them floating in the chilly water for 2+ hours before being rescued by the authorities? As I reflected on it, and after my initial incredulous reaction, my conclusion was that it made perfect sense to each of them to do what they did. In the moment, each of their contexts led them to make what to me seemed in hindsight to be a very foolish and costly decision. You may be asking yourself….” What is he talking about? How could it make sense to do something so obviously foolish?” Let me attempt to explain. Context is powerful and it is the primary source we have when making decisions. Additionally, it is individual-centric. My context, your context and the context of the individual who drove around a barricade into twenty feet of water are all very different, but they are our personal contexts. In my context where I am sitting in my living room, watching TV, sipping a cup of coffee, with no pressure to get to a certain location for a specific purpose is most likely completely different from the man who drove around a police vehicle, with flashing lights, in a downpour, with his windshield wipers flashing, on his way to check on someone he cares about and who could be in danger from the rising water. What is salient to me and what was salient to him are very different and would most likely lead to different decisions. His decision was “locally rational”, i.e. it made perfect sense in the moment. We will never know, but it is very likely that his context precluded him from even noticing the flashing lights of the police vehicle or the possibility of water in the underpass. It is also possible that “human error” was present in the tragic deaths of at least 6 people during the flood, but human error is not a sufficient explanation. We can never really understand what led to their decisions to put themselves at risk without understanding the contexts that drove those decisions.

This is what we really need to focus on when we are investigating incidents in the workplace so that we can impact the aspects of contexts that become salient to our workers. The greater impact we have on minimizing the salience of contextual factors that lead to risk taking and increasing the salience of contextual factors that minimize risk, the greater opportunity we will have to end “senseless” injury and death in the workplace, and on rain swollen highways. This approach will have a lot more positive impact than just chalking it up to “stupidity”!

Distracted Driving: I Teach This Stuff and I Still Mess It Up

My oldest son just turned 15 so my wife and I started researching the different avenues for teen driver’s education available in our town. With a handful of options we decided to take the route of “parent taught driver-ed” as it was the most convenient, cost effective, and we felt we were quite capable of taking on the task. After all, my wife is a teacher and I research and train people about performance in complex systems. Additionally, I have developed our online training platform, which is the medium in which most of the classroom driver-ed learning will take place. “We’ve got this,” I remember telling her. As we have progressed in our program, he has become more and more capable and comfortable in not only the rules of the road, but also driving in our small Dallas/Ft. Worth suburb. But just a couple of days ago I was smacked in the face by reality when we stopped at a red light and he instinctively reached into his pocked to retrieve his cell phone to read a text he just received from his girlfriend. How could he be so irresponsible with all he’s learned? How could he possibly think this was okay to read texts while behind the wheel? His response: “You always check your phone at red lights so I just figured it wasn’t a big deal”!

Yes, I teach this stuff and yes I mess it up on a consistent basis when I’m not intentional about what I know to be true.

For those of you that frequently read our blogs you know that we talk about complexity, the impact of context on performance, and how the model provided by others impact the performance of those around them in surprisingly unforeseen ways. You are also aware of the studies about using cell phones to talk and text and the impact that these actions have on the ability to operate a vehicle. We have been accustomed to seeing anti-texting commercials and even live in communities that have laws, with fines attached, preventing the use of cell phones while driving. Yet some of you, and some of us who teach this stuff, still glance down at the phone when we hear the ding or even pick up the phone when that all important call finally comes while we are driving.

A recent study shows that after a decade of car related deaths declining year after year, a steep increase of almost 10% occurred in 2015. Could this be an anomaly or a sign of something far more troubling occurring? While no data has yet pointed to any trend in automobile fatality causation, I do have have my own theories and anecdotal data that I will share.

Smart phones have only been around for a little over a decade now and they are getting smarter and smarter with each launch. We all remember the blinking red light of the blackberry that screamed out to us, “Read me!” Today our phones have Facebook messenger, LinkedIn alerts, text, iMessage, email, and bluetooth and our cars have mobile apps and wifi hotspots. We are constantly being alerted that somebody wants to talk to us right now. It’s like that blinking red light on steroids. The good news is that local governments and other organizations saw this coming years ago so they implemented laws and launched public service announcements and signage by the roads, warning us of the dangers these devices present. And as any good safety professional knows, making new rules and putting up signs that scare people works…for awhile.

Where I have failed as a driver-ed instructor, and father, is that I kept my phone within reach. It was in my pocket, sitting in my cup holder, or holstered on that clamp attached to my A/C vent that I bought at Best Buy so that I could use the navigation app twice a year. Based on what we know about complexity, context, Human Factors, Human Performance, or whatever current science we want to throw out there, the answer is easy. Turn the phone off, put it in the glove compartment and drive. It doesn’t take any research or a consultant to come up with this idea; in fact, it’s something that a lot of people have figured out already. Take the blinking red light, the text ding, or the “silent” buzz away from our attention and our attention remains on the road where it belongs.

I will leave you with this last thing. Again, nothing groundbreaking here but a fun example about how those devices that are designed to make our lives so much better have effected our performance in fascinating ways. A recent study at the Western Washington University shows that people walking and talking on their cell phones noticed a clown on a unicycle directly next to them only 25% of the time, while those walking and not on a phone noticed the clown over half of the time. But more impressively, those walking in pairs noticed the clown 75% of the time. If you are interested, here is a link describing this research: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ysbk_28F068

Complexity, Age and Performance

We live and work in environments that are continuously increasing in complexity, which puts an even greater strain on our ability to make quick, accurate decisions. (See Human Error and Complexity: Why your safety “world view” matters). Among the many important considerations for organizational leaders is how age affects people’s decisions and performance in these complex environments. Though the cognitive and socio-emotional skills of younger workers (under 25 years of age) are still developing (see Protecting Young Workers from Themselves), this group is at its peak performance with respect to speed of information processing and physical abilities…including vision, hearing, strength, flexibility and reaction time.

On the other hand, the opposite is generally true of the 55+ age group, even though there are individual differences. Aging tends to bring with it a decline in just about all of these physical abilities as well as some cognitive abilities. (Note that we are talking about “normal” aging, absent significant pathology such as Alzheimers and Dementia.)

While research has demonstrated that aging has little or no effect on general intelligence, it can impact other aspects of cognition. The aging brain is slower to shift attention to new stimuli in the environment and also slower to recall uncued relevant information. Additionally, short term (“working”) memory functions less efficiently with age. While an older worker might make fewer mistakes in decision making, he or she will normally require more time to make those decisions. So when a task is complex and requires the manipulation of information or ignoring irrelevant information, there may be age related decline in performance (e.g., Balota, et al, 2000), especially when the older person is under pressure to perform. In short…

Complexity + Time Pressure = Kryptonite for the Aging Brain

Left at that, it would be bad news for the aging worker in our increasingly complex and fast-paced world. HOWEVER, as with nearly everything in life, there are more pieces to this puzzle. Two of these pieces are experience and contextual cues. Research has shown that older adults tend to perform well on recognition tasks where contextual cues are present. This could help explain their lower incident rate relative to younger workers, since older adults recognize and process contextual cues effectively because of their past experience. They are more likely to recognize a hazard as a hazard because they have experienced it in the past. In short…

Contextual Cues + Experience = The Great Equalizer

Adolescents and young adults don’t have the experience with contextual cues that older adults do, so they are less likely to recognize them and respond to them. Younger workers’ higher speed of processing is offset by their lack of experience with contextual cues…and vice versa with older workers. These findings provide additional support for the need to have older and younger workers learn to work together so as to capitalize on their age-related strengths. In short…

Older Workers + Younger Workers = Better Decisions

Unfortunately, there are common and misguided stereotypes about both younger and older workers, which can keep us from honestly exploring the many ways that they may contribute to organizational success. Understanding the truth about the developing brain of younger workers and the aging brain of older workers may just be a key to thriving in our increasingly complex world.

Protecting Young Workers: Bridging the Age Gap in the Workplace

In a recent blog (Protecting Young Workers from Themselves) we discussed some of the reasons for the relatively high risk tolerance of young (15-24 years old) workers compared with older workers. We concluded that while there is still cortical structure development during this developmental period that this alone does not explain why this age group is at a higher risk of engaging in unsafe actions and suffering the consequences of those actions. The research demonstrates that the less developed limbic system which is involved in both social and pleasure seeking behavior can at times override the logical capabilities of the young workers and stimulate them to engage in risky behavior. Because educational programs designed to provide the young workers with the knowledge necessary to effectively interpret their contexts has not proven overly successful, we proposed that one way to impact their risk taking in the workplace is to remove social stimuli such as peers from their work teams and replace them with older, more risk averse and experienced workers, especially those in the 55+ age group. We suggested that these older workers who understand and can interpret the various workplace contexts could provide mentoring and coaching for the younger workers. This however introduces another set of issues that must be addressed if this approach is to have the desired impact. These issues include the perceptions/stereotypes/expectations of each cohort group by the other and the skills necessary to impact those perceptions/stereotypes/expectations. We all have a tendency to focus on actions and traits of other people that fit with our expectations and stereotypes of the groups to which that person belongs, including the person’s age. We also tend to behave toward that person based on what we perceive them doing and they do likewise to us. The problem is that what we “see” is driven by what we “expect to see” and often results in a phenomenon known as the “Self-Fulfilling Prophecy (SFP)” which also reinforces our stereotypes and thus our future interactions. For example, an older worker observes a younger worker engage in some risky behavior and because the older worker views younger workers as thinking they are “bullet proof” he immediately criticizes the younger worker for his failure to “think”. The younger worker who did what he thought was the right thing in the situation becomes defensive toward the “judgmental/rude” older worker and “smarts off” to him. This causes the older worker to become defensive and the cycle continues, reinforcing the SFP and strengthening the stereotypes held by both individuals (see “Your Organization’s Safety Immune System (Part 2): Strengthening Immunity” for a more in-depth discussion of defensiveness).

The question is how do we utilize the older workers as coaches for the younger workers without the negative impact of the SFP? The key is to change the expectations that both age groups have of each other and this requires training. Facilitated, interactive training programs that address the common impact of the SFP, help people of all ages understand the role of individual differences in performance, teach people how to deal with the Defensive Cycle™, and give them opportunity to interact successfully with each other tend to produce environments where both older and younger workers can capitalize on the strengths that each bring to the table. While younger workers bring less socioemotional maturity and experience, they also bring creativity, physical strength and a fresh view of the work context. Older workers bring the experience and a broader understanding of the work context that can help younger workers make better, less risky decisions. The key is mutual understanding and mutual respect which come from less stereotyping, less defensiveness and more teamwork.

Are Safety and Production Compatible?

Can we all agree that people tend to make fewer mistakes when they slow down and, conversely, make more mistakes when they speed up? And people tend to increase their speed when they feel pressure to produce? Personal experience and research both support these two contentions. Deadlines and pressure to produce literally change the way we see the world. Things that might otherwise be perceived as risks are either not noticed at all or are perceived as insignificant compared to the importance of getting things done. Pressure and Perception

A famous research study by Darley & Batson (1973), sometimes referred to as “The Good Samaritan Study”, demonstrated the impact of production pressure on people’s willingness to help someone in need:

Participants were seminary students who were given the task of preparing a speech on the parable of the Good Samaritan — a story in which a man from Samaria voluntarily helps a stranger who was attacked by robbers. The participants were divided into different groups, some of which were rushed to complete this task. They were then sent from one building to another, where, along the way, they encountered a shabbily dressed “confederate” slumped over and appearing to need help. The researchers found that participants in the hurry condition (production pressure) were much more likely to pass by the person in need, and many even reported either not seeing the person or not recognizing that the person needed help.

Even people’s deeply held moral convictions can be trumped by production pressure, not because it has eroded those convictions, but because it makes people see the world differently.

The Trade Off

One reason for this is that many of our decisions are impacted by what is known as the Efficiency-Thoroughness Trade-off (ETTO) (Hollnagel, 2004, 2009). It is often impossible to be both fast and completely accurate at the same time because of our limited cognitive abilities, so we have to give in to one or the other.

When we give in to speed (efficiency) we tend to respond automatically rather than thoughtfully. We engage what Daniel Kahneman (see Hardwired to Jump to Conclusions) refers to as “System 1” processing — we utilize over-learned, quickly retrieved heuristics that have worked for us in the past, even though those approaches cause us to overlook risks and other important subtleties in the current situation. This is how we naturally deal with the ETTO while under pressure from peers, supervisors or organizational systems to increase efficiency.

Conversely, when we are not under pressure to increase efficiency, but, rather, pressure to be completely accurate (thorough), we have a greater tendency to engage what Kahneman calls “System 2” processing — we are more thorough in how we manage our efforts and account for the factors that could impact the quality of what we are producing. In these instances, we will notice risks, opportunities and other subtleties in our environments, just as the “non-rushed” participants did in the “Good Samaritan Study.”

So what is the point?

Most of our organizations are geared to make money, so efficiency is very important; but how do we bolster the thoroughness side of the tradeoff to support safety and minimize undesired events? To answer this, we have to take an honest look at the context in which employees work. Which is more significant to employees, efficiency or thoroughness? And what impact is it having on decision making?

Some industries (e.g. manufacturing) have opted to streamline and automate their processes so that this balance is handled by interfacing humans more effectively with the machines. Some industries can’t do this as well because of the nature of their work (e.g., construction). We worked with a client in this later category that had a robust safety program, experienced employees and well intentioned leaders, but which was about to go out of business because of poor safety performance…and it had everything to do with the Efficiency-Thoroughness Trade-off. The contracts that they operated under made it nearly impossible to turn a profit unless they completed projects ahead of schedule. As they became more efficient to meet these deadlines, the time-to-completion got shorter and shorter in each subsequent contract until “thoroughness” had been edged out almost entirely. For this company, preaching “safety” and telling people to take their time was simply not enough to outweigh the ever-increasing, systemic pressure to improve efficiency. The only way to fix the problem and balance the ETTO was to fix the way that contracts were written, which was much more challenging than the quick and illusory solutions that they had originally tried.

Every organization is different, so balancing the ETTO will require different solutions and an understanding of the cultural factors driving decision making at all levels of the organization. Once you understand what is salient to people in the organization, you can identify changes that will decrease the negative impact of pressure on performance.

The Brain Science of Human Performance: Part 2

In our last post, "The Brain Science of Human Performance", I described how three inherent functions of the brain affect the performance of people in very real ways. These three functions are problem solving, automation, and generalizing. I also introduced another mechanism of the brain that can inhibit performance, cognitive biases. In this followup, I will propose a way to overcome the cognitive biases and use the three functions in a strategic manner to drive good performance. As I detailed before, our brains take in an enormous amount of data when we are trying to problem solve a new and/or difficult task. This data is comprised of many factors that we call our "context". The most salient (important) and obvious factors actually create a feeling of what makes sense in that moment and is referred to as "Local Rationality". Once we complete the task and it seems to be successful we eventually automate this process and it becomes part of our normalized routine. We then, without even realizing it, assume that if that process worked in that case, then it must be the right thing to do in other, similar, cases and this is where the "generalizing" comes into play. While this may seem like an inherent flaw, those that understand this process are able to actually use it to create better performance. We know that our brains kick in when we have to start processing new context. If we can identify the context that was previously in place (i.e., that created a moment of local rationality for performing in a flawed way) we can change that context to be more conducive to better performance. For example, an operator at a manufacturing facility has found a way to reach around a guard and remove product that has become lodged in the machinery. He doesn't perform lockout/tagout (LOTO) because the main power source is across the facility and it takes more time to walk over there and lock and tag than it does to perform his work-around. He also knows just where to insert his arm to reach around the guard and pull out the product. He's not the only person doing this, as many other operators have been performing it that way in this facility for years. In fact, it's just how they do things around there, and after all nobody has ever been hurt doing it this way and, additionally, they have certain levels of production that they must maintain to keep their supervisors off their back. While that may seem like a very mundane and simple example of what happens in countless facilities everyday, it is actually rooted in an incredibly complex cognitive system. While most of you can see an immediate fix or two (move the power source and create a better guard) let's understand how that actually affects the brain. If we are able to get budget approval (sometimes difficult) to move the power source and fabricate a better guarding system, then we would have a new and salient context. If the operator can't reach through the guard, then he would be required to remove the guard, therefore removing the guard becomes the logical, but time consuming thing to do. If, however, de-energizing the machinery is easier and requires less time, then it becomes far more likely that he will actually do that, not because he's lazy but because we've just impacted a cognitive bias that I'll explain later. Once this context is changed, the cognitive automation stops and we move back to problem solving. Based on the new context, a different way of doing things becomes locally rational and once that new, and better way of performing the task is successful, that performance will then become automated and generalized.

Unfortunately, our work isn't yet complete, we also have to deal with those pesky cognitive biases (distortions in how we perceive context). I mentioned above that a person may chose to skip LOTO because it takes more time to walk across the facility than to perform the actual task. This is rooted in a cognitive bias called "Unit Bias" where our brains are focused on completing a single task as quickly and efficiently as possible. Or how about the "bandwagon effect" which is the tendency to believe things simply because others believe it to be true. There is also "hyperbolic discounting" which is the tendency to prefer the more immediate payoff rather than the more distant payoff (completing a task vs. performing the task in a safe way), and the list goes on. To overcome these cognitive biases we must first become aware that they exist. Our brain is wired in a way that these biases are a core function. To begin to rewire the brain and overcome these biases we must understand these biases and with this awareness we are actually less likely to fall victim to them. When we fail to do this we are actually falling victim to yet another cognitive bias that is called "Bias blind spot".

So what is the take-away from all of this? Our brains are wired to function as efficiently as possible. One of the ways we do this is to automate decision making and performance to maximize efficiency. Our decisions are driven by our contexts and the sometimes distorted way that we view that context. If you want to change unsafe performance you have to change the context and the way we view our context so that it becomes locally rational to perform in a safe manner. If we don't change the context we will continue to get the same performance we have always gotten because that is just the way our brains do it.

The Brain Science of Human Performance

Have you ever experienced the mental anguish of trying to perform a new and complex task? Something that requires so much mental and maybe even physical dexterity that it takes you a while to problem solve and get it right? I would imagine that most of us have experienced this innumerable times in our lives and, if replicated enough times, that task eventually becomes something of a second nature. This concept was actually captured quite well by Daniel Kahneman in his book “Thinking, Fast and Slow”. Kahneman talks about this second nature mental tasks as System I thinking and the more complex and process heavy tasks as System II. Put simply, things that we do without even really thinking about it, like a skilled typist putting her fingers on the correct keys when she constructs an email, as System I tasks. However, a person new to typing would have to try to remember where each key is located or maybe even look at the keyboard itself to find that ever elusive “X” key and this type of processing would be System II thinking. Understanding Kahneman’s description of System I and System II thinking, however, is only a part of the brain science of human performance. As we like to say it, the human brain does three things repetitively and expertly; Problem Solve (System II), Automate (System I), and finally generalize, and it does all of this while interfacing with the world in a sometimes distorted manner.

Let’s see if we can break this down somewhat sequentially, although much of this happens simultaneously in the real world. Problem solving a new task at work, as mentioned before, can be complex and mentally taxing. You see, our brains are taking in all of the relevant information in performing this task while also trying to process extraneous context such as peer approval, time pressures, available resources, family issues, what’s for dinner, etc., etc. Once all of this data is processed and the task is completed successfully our brain feels like the problem solving job is completed and wants to move on to the next task. This is where automation comes in.

The human brain really isn’t capable of multi-tasking at any level of effectiveness. While it may perform multiple tasks at the same time, it can’t really process two System II tasks simultaneously. Therefore it wants to automate tasks (System I) so that it can be ready for the next System II task. Automation may take time to fully take hold but once it does it is often communicated as, “this is how I’ve always done it” or “that’s just how we do things around here”, but at some point that task was new and a System II process. The problem with automation is that we don’t realize that we are in automation. We don’t feel the mental strain of these automated tasks and don’t even realize that we are involved in them hundreds, maybe even thousands of times a day. But our brain isn’t finished trying to be efficient, not only does it want to automate tasks, it also wants to generalize tasks or behaviors that seem to be somewhat related. Basically our brain says, “if that works here then it must work there as well”. In that moment of trying to be super efficient our brains have bypassed the entire problem solving process for future tasks that seem to be related to the automated tasks that we have already problem solved. This would seem to be highly efficient, but it can also lead to errors. In two weeks we’ll revisit a previous topic…..the distorted view of context in the problem solving process (cognitive biases)…..and then also examine how we can make this brain science work in our favor.

Stress and Human Performance

If you examine the research literature on the topic of “psychological stress” you will find that there is a lot of disagreement on a definition of that term. However, there is almost total agreement that while stress can have positive effects in some situations, it can also have very negative effects on human performance in other situations. For our purposes we will accept the Mirriam-Webster definition of stress as “a state of mental or emotional strain or tension resulting from adverse or very demanding circumstances.” While this definition ignores the positive effects of moderate stress that research shows is needed for motivation and action, it does describe a state that we all have experienced, and some of you may be experiencing right now. Stress comes in several forms, including acute stress (in an emergency situation), chronic stress (from factors such as job, family, etc), stressful life events (e.g., divorce, death of a loved one, etc) and just those daily hassles (e.g., traffic, arguments, etc). The one common thing in all of these types of stress is that they originate as a response to context. There’s that word again….the one that we seem to talk about in just about all of our blogs. Not only is stress a response to various aspects of our context, stress becomes part of our context and then impacts our performance and the decisions that we make. Stress is our physiological response to our interpretation/appraisal of our context and it directly impacts cognition, social behavior and general performance. Salient contextual factors such as noise, peer pressure, authority pressure, task load and time pressure have been shown to have detrimental impact on performance. Research is clear that high levels of stress cause us to narrow our attention span, decrease search behavior, react slower to peripheral cues, reduce our vigilance, degrade problem solving and rely on over learned responses that may or may not be best in the current situation. In other words, we tend to make poorer decisions that can lead to failure and even injury. Stress also causes us to lose our team perspective and it decreases the frequency with which we provide help to others. This is especially impactful when working in high risk environments where watching your partners back and intervening when necessary is critical to maintaining safety and stopping unsafe actions and incidents.

So how do we deal with this so that stress doesn’t negatively impact performance?

We suggest a two-pronged approach involving (1) control of context and (2) control of how we interpret context in the moment. Keep in mind that we are talking about normal stress reactions that we all experience, not pathological reactions that are best dealt with by trained therapists. Let’s start with control of context and let’s set that context in the workplace. In the workplace, context is, to a large extent under the control/influence of supervision and management. So what should supervisors and managers do? They should attempt to set realistic production objectives with realistic time constraints to create a context that help control stress produced by task load and time pressure. They should minimize where possible the amount and duration of noise. They should make sure that employees are trained so that they have the knowledge and skills required to meet those production objectives. Simply being aware of the negative impact of stress, the relationship between stress and context, and the impact that they personally can have on that context will go a long way in stress control. But what about how the individual interprets context in the moment. Simple awareness that we can control stress reactions through our interpretation of context is a very good starting point. In our February 25, 2015 blog we discussed how we are “Hardwired to Jump to Conclusions”. In that discussion we saw how research supports the involvement of two different cognitive “Systems” in decision making and that System 1 tends to make quick decisions based on past experience and System 2 tends to be more rational and analytic. Research demonstrates that the more stress we are experiencing, the more likely we are to engage in System 1 thinking which increases the likelihood that we will make less informed and perhaps less effective decisions. We suggest that you use the initial physiological stress reactions as a “trigger” to stop, engage System 2 cognitive functions and evaluate your current context to determine what, if anything, can be done to create a different, less stressful context. But what if you can’t change the context? As we all know, there are times when we have a deadline and we are stuck in traffic and we can’t change that. But we can stop, engage System 2 thinking, slow down our physiological response, realize that stressing out is not going to change the situation and figure out the best way out of this situation. This of course takes practice and there are times when we won’t be successful, but understanding stress and how to respond to it can become an effective strategy to help us perform effectively in stressful conditions.

Sustaining Good Performance

We have spent a lot of time talking about the side of accountability that involves correcting failure. But if you will recall our discussion in January, accountability actually involves an examination of the facts/reasons underlying a specific event/result (accounting) followed by the application of appropriate consequences for those actions and results in an attempt to more predictably have success going forward. In other words, accountability involves first the identification of both failure and success, followed by an examination of the underlying reasons for the failure/success and then the determination of the appropriate consequences to help sustain the success or eliminate the failure in the future. This month we would like to discuss the appropriate application of consequences following success so that we will have a greater chance of sustaining good performance going forward. But why is this important anyway? When we ask supervisors/managers what they really want from their employees we get a very consistent response…..”We want employees who give us good results and who take initiative!” My response to this is that the two are highly interrelated. Let me explain what I mean by this. People who take initiative are people with high levels of Self-Esteem or Self-Confidence which is developed from meaningful (to the person) accomplishment followed by recognition by someone significant to the individual. In most cases the supervisor/manager has a significant level of control over both of those variables, i.e. they control the tasks that the employee is allowed to engage in, they control recognition and they are significant to their employees (in most cases). Obviously, for success to occur while engaging in meaningful tasks, there needs to be support through training, necessary resources, etc. and when success occurs there needs to be the appropriate application of recognition, or what psychologists call “reinforcement”. Reinforcement by definition is a consequence that when following a behavior increases the likelihood that the behavior will reoccur in the future. If that reinforcement is recognition by a significant person then it will also serve the function of increasing self-confidence and the likelihood of initiative. It is important that the recognition follows some important guidelines however. Let’s look at four important aspects of reinforcement; What, When, Where and How.

WHAT. The rule here is to reinforce the behavior/performance that you want to continue and not the person. This focus on behavior ties the reinforcement to that behavior in the future and is what increases it’s chances of reoccurrence. This will also act to increase self-esteem even though you do not focus on the individual. For example, saying….”Thank you. You got that report in on time and with no errors” is much more effective than, “Thank you. You are becoming a very reliable employee.” While the latter may make the person feel better, it does nothing to point out exactly what you want going forward.

WHEN. Reinforcement is not always appropriate as we will discuss below, but when it is it has been demonstrated that reinforcement that immediately follows an action is in most cases the most powerful and effective. While some delay may be necessary in some cases, waiting until the annual performance appraisal is certainly not the best option.

WHERE. While failure should always be redirected in private, success should be reinforced in public in most cases. Public recognition does two things, it makes the person look good in front of peers and at the same time demonstrates your expectations to others on your team. It must always however be appropriately done as we will discuss below.

HOW

- Keep it brief and simple. It should, in most cases take only a few words and therefore a few seconds to reinforce performance. If you feel it is necessary to explain in more detail the exact performance/result then do so, but don’t carry on forever. You will lose the person’s attention and perhaps even embarrass the person in front of peers.

- Be genuine. Let the person know that you truly appreciate their success and expect it to continue into the future. Sarcasm has no place in the application of reinforcement.

- Make it appropriate to the level of performance. Most of the time a simple “thank you” with a connection to the successful performance is appropriate, but when the result is significant and worthy of additional recognition, just make sure that it fits. For example, if the person has contributed beyond expectations and their impact has had a noticeable impact on revenue, then a bonus might be in order. Failure to evaluate the appropriateness of recognition could lead to reduced performance in the future.

- Be consistent among employees. While meaningfulness varies among employees the need for recognition doesn’t. Make sure that you find what is meaningful for each employee and apply recognition where appropriate in a consistent manner.

- Avoid scheduled or predictable recognition. Psychological research shows that variable (unpredictable) reinforcement is more effective for behaviors that have been learned. While teaching a skill the application of continuous reinforcement is best, but after the skills is learned change to a less frequent, less predictable schedule and you will find that employees will be successful for a longer period of time.

What’s the point?

Sustained successful performance accompanied by initiative requires self confidence. Meaningful accomplishment followed by recognition by a significant person helps to create that self confidence and thus sustained success. If you are a supervisor (or a parent) you have more control over this process than you might imagine.

Human Error and Complexity: Why your “safety world view” matters

Have you ever thought about or looked at pictures of your ancestors and realized, “I have that trait too!” Just like your traits are in large part determined by random combinations of genes from your ancestry, the history behind your safety world view is probably largely the product of chance - for example, whether you studied Behavioral Psychology or Human Factors in college, which influential authors’ views you were exposed to, who your first supervisor was, or whether you worked in the petroleum, construction or aeronautical industry. Our “Safety World View” is built over time and dramatically impacts how we think about, analyze and strive to prevent accidents.

Linear View - Human Error

Let’s briefly look at two views - Linear and Systemic - not because they are the only possible ones, but because they have had and are currently having the greatest impact on the world of safety. The Linear View is integral in what is sometimes referred to as the “Person Approach,” exemplified by traditional Behavior Based Safety (BBS) that grew out of the work of B.F. Skinner and the application of his research to Applied Behavioral Analysis and Behavior Modification. Whether we have thought of it or not, much of the industrial world is operating on this “linear” theoretical framework. We attempt to understand events by identifying and addressing a single cause (antecedent) or distinct set of causes, which elicit unsafe actions (behaviors) that lead to an incident (consequences). This view impacts both how we try to change unwanted behavior and how we go about investigating incidents. This behaviorally focused view naturally leads us to conclude in many cases that Human Error is, or can be, THE root cause of the incident. In fact, it is routinely touted that, “research shows that human error is the cause of more than 90 percent of incidents.” We are also conditioned and “cognitively biased” to find this linear model so appealing. I use the word “conditioned” because it explains a lot of what happens in our daily lives, where situations are relatively clean and simple…..so we naturally extend this way of thinking to more complex worlds/situations where it is perhaps less appropriate. Additionally, because we view accidents after the fact, the well documented phenomenon of “hindsight bias” leads us to linearly trace the cause back to an individual, and since behavior is the core of our model, we have a strong tendency to stop there. The assumption is that human error (unsafe act) is a conscious, “free will” decision and is therefore driven by psychological functions such as complacency, lack of motivation, carelessness or other negative attributes. This leads to the also well-documented phenomenon of the Fundamental Attribution Error, whereby we have a tendency to attribute failure on the part of others to negative personal qualities such as inattention, lack of motivation, etc., thus leading to the assignment of causation and blame. This assignment of blame may feel warranted and even satisfying, but does not necessarily deal with the real “antecedents” that triggered the unsafe behavior in the first place. As Sidney Dekker stated, “If your explanation of an accident still relies on unmotivated people, you have more work to do."

Systemic View - Complexity

In reality, most of us work in complex environments which involve multiple interacting factors and systems, and the linear view has a difficult time dealing with this complexity. James Reason (1997) convincingly argued for the complex nature of work environments with his “Swiss Cheese” model of complexity. In his view, accidents are the result of active failures at the “sharp end” (where the work is actually done) and “latent conditions,” which include many organizational decisions at the “blunt end” (higher management) of the work process. Because barriers fail, there are times when the active failures and latent conditions align, allowing for an incident to occur. More recently Hollnagel (2004) has argued that active failures are a normal part of complex workplaces because of the requirement for individuals to adapt their performance to the constantly changing environment and the pressure to balance production and safety. As a result, accidents “emerge” as this adaptation occurs (Hollnagel refers to this adaptive process as the “Efficiency Thoroughness Trade Off”) . Dekker (2006) has recently added to this view the idea that this adaptation is normal and even “locally rational” to the individual committing the active failure because he/she is responding to a context that may not be apparent to those observing performance in the moment or investigating a resulting incident. Focusing only on the active failure as the result of “human error” is missing the real reasons that it occurs at all. Rather, understanding the complex context that is eliciting the decision to behave in an “unsafe” manner will provide more meaningful information. It is much easier to engineer the context than it is to engineer the person. While a person is involved in almost all incidents in some manner, human error is seldom the “sufficient” cause of the incident because of the complexity of the environment in which it occurs. Attempting to explain and prevent incidents from a simple linear viewpoint will almost always leave out contributory (and often non-obvious) factors that drove the decision in the first place and thus led to the incident.

Why Does it Matter?

Thinking of human error as a normal and adaptive component of complex workplace environments leads to a different approach to preventing the incidents that can emerge out of those environments. It requies that we gain an understanding of the many and often surprising contextual factors that can lead to the active failure in the first place. If we are going to engineer safer workplaces, we must start with something that does not look like engineering at all - namely, candid, informed and skillful conversations with and among people throughout the organization. These conversations should focus on determining the contextual factors that are driving the unsafe actions in the first place. It is only with this information that we can effectively eliminate what James Reason called “latent conditions” that are creating the contexts that elicit the unsafe action in the first place. Additionally, this information should be used in the moment to eliminate active failures and also allowed to flow to decision makers at the “blunt end”, so that the system can be engineered to maximize safety. Your safety world view really does matter.

All They Care About Is Money!

Actually, research has consistently shown that while salary increase is important, it is usually far down the list of reasons why employees decide to leave for another job. Significantly more people leave because they want more or new challenges, they are not happy with how they are treated by their current supervisor or they believe their contributions are not valued. Money is obviously important because it allows us to meet our basic needs and achieve some of our life goals, but it may not be as important as other factors that are in the direct control of supervisors.

Using Extrinsic Motivators Effectively

The best supervisors understand that money is just one of the extrinsic motivators that they have at their disposal and that the way they use these motivators is more important than the motivators themselves. Because of this, they follow what we call “The Contingency Rule” in the application of all extrinsic motivators. So what is this rule?

The Contingency Rule: Tie the extrinsic motivator to performance. Extrinsic motivators that supervisors have at their disposal include such things as money, praise, job assignments, training opportunities, etc. Making the receipt of any of these contingent on successful performance is critical to their motivational impact. For example, it has been well documented that cost of living increases act as a satisfier and not as a motivator because they are not tied to performance. It could be argued that not receiving an expected cost of living increase could act as a motivator to look for another job, but in this case it would be a de-motivator for improved performance in the current job.

"Best Bosses" are clear about what they expect from employees, and they are also clear about the relationship between accomplishment of those expectations and extrinsic motivators. When people know that successful performance leads to increase in pay, praise, desired job assignments, etc, they are much more likely to put out the effort required to receive those things. Failure to understand these contingencies will only lead to employee confusion, dissatisfaction and lowered motivation. It might also lead the person to look for another job.

Conflicting goals make room for performance failures

Most people do not set out to fail. On the contrary, most of us regularly attempt to succeed; but at times we do fail none-the-less. The role of a supervisor is to get results through the efforts of other people, so an important question for supervisors is, “Why does a specific performance failure occur?” There are a lot of reasons - knowledge, skill, motivation, etc. - and key among them is something called “goal conflict”.

We live in a complex work-world with multiple competing demands. We must be safe, fast, cheap and valuable all at the same time. It is humanly impossible to make all of these goals #1 at the same time, so we make cost-benefit tradeoffs and “choose” which objective is the most important at the time given the pressures of the environment/culture that we are in. I may choose to “hurry” because of time pressure, but in so doing sacrifice safety and quality.

As a supervisor I need to understand the drivers behind employees’ performance failure before I can adequately help them become successful. What “tradeoffs” did the employee make that produced the failure? Did his desire to “please” the supervisor outweigh his calculation of his own skill-level? Did her perceived pressure to produce outweigh the thought to evaluate hazards associated with the task and take precautionary action?

Unless we as supervisors take the time to evaluate the conflicting goals that drive employees’ performance, we will be less effective in reducing the opportunity for failure.

You Might Not Always Get What You Want

What does it mean to have a "Formal Culture" and an "Informal Culture"?

Have you ever instituted a new policy or procedure into your organization, spent countless hours and dollars trying to drive the initiative throughout the organization, only to see it fall flat? Organizations large and small face a similar problem -- how to make their organization become what they envision it to be.

When organizational experts refer to the overall performance of an organization, they often use the word “culture”. While there is disagreement on the exact definition of organizational culture, most would agree that it includes the values and behaviors that the majority of participants engage in; what most of the people believe and do most of the time. This is called the “informal culture” as compared to the “formal culture”, or what the leadership wants the culture to be. It makes no difference if your organization is a large corporation, a small “mom and pop”, a non-profit, or an educational institution, each of you have a formal and informal culture. One aspect of great organizations is that they close the gap between the two cultures so that “what’s going on - out there” very much resembles the vision of leadership.

“Informal Culture is what most of the people believe and do most of the time.”

You may wonder if these great organizations close this culture gap by hiring the “right people”, or if they do something more intentional to close this gap. The answer quite simply is both. Great organizations start with great people, but they also understand and affect the other aspects of their culture.

The Best Organizations

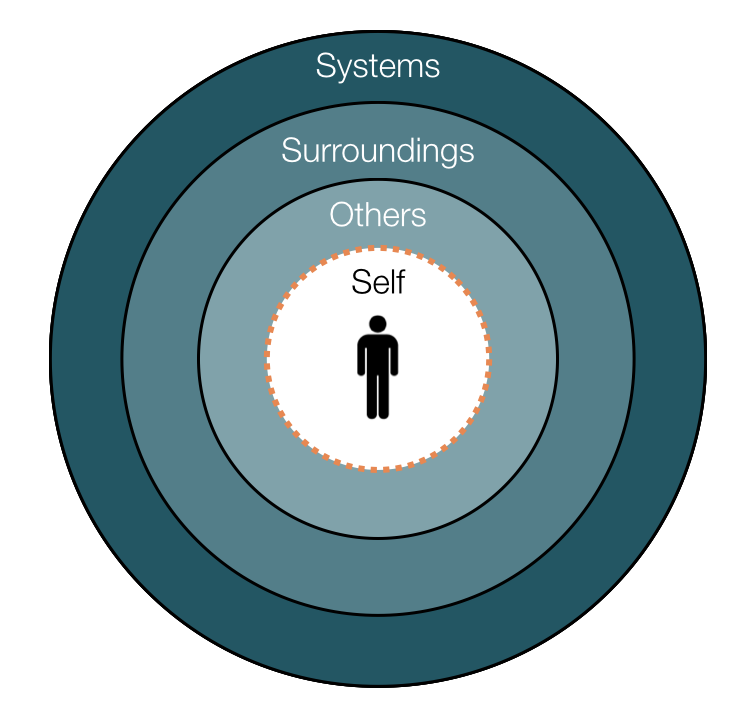

The best organizations don’t stop with simply creating rules and policies, they do much more to impact the everyday behavior of their employees. If you’ll refer back to our August 2012 Post on the role of contextual factors in industrial safety incident prevention, the very best bosses and organizations understand that human performance is a result of complex systems. Organizational factors such as rules, policies, and reward systems are only a portion of the complex system that drives human performance. The best organizations understand that it is also people, both the individual and intact teams, plus surroundings that drive their overall performance. If the employee base has failed to implement a new directive from leadership, there could be several reasons affecting this. It could be that employees don’t understand the new initiative, operational pressures contradict the initiative, they don’t have the equipment necessary to make it happen, or a myriad of other factors. The very best organizations are those that are able to gather field intelligence detailing actual performance and factors driving the performance, and then institute corrective measures that enable the workforce to align their own performance with the vision of leadership.

So what does that mean for you if you are in an organization with a gap between your formal and informal cultures? We would first encourage you to perform a cultural analysis to get a better understanding of your informal culture. With this knowledge you will be able to understand what contextual factors are driving the performance of your employees. This information will allow you to initiate corrective measures to close the gap between your formal and informal cultures. The best organizations don’t make the mistake of simply focusing on changing people, they focus on the entire context to enable those on board to perform to a higher standard.

Dreaming of Greener Pasture

How do I find personal satisfaction in an organization that doesn't seem interested in being effective?

This is a very important question for all of those who have spent time working in seemingly heartless or meaningless organizations. In January’s newsletter we defined an effective organization as one that meets its stated goals and accomplishes its stated mission. But of course, by this definition, low goals and unimportant missions can create effectiveness and this would miss the point, therefore we add that effective organizations are those where the mission and goals are ones that people would want to invest in and/or participate in because they bring value to not only the individual, but also customers and society in general.

So what about the employee who is stuck in an organization that doesn’t seem to meet these criteria? The easy answer is to simply quit and find a better organization. While this may seem to be the prudent decision, is it the right one? Let’s now refer back to the original question and focus on a key word in the question - “seem”. Often times employees can only guess as to what their organization’s goals and mission may be because they have not been clearly articulated (our February Newsletter topic). Until one clearly understands where leadership is wanting to take the organization, employees should not make bad guesses about their willingness to be effective. This is where candid and frank conversation with leadership is critical to clearly understand the mission.

For argument’s sake, let’s make the assumption that the employee is actually working in an organization that simply has no intention of meeting our definition of an effective organization. How do we find personal satisfaction without simply leaving for greener pastures? At this point the employee needs to focus on what they can control and influence within the organization. They have control over their own performance and influence over the performance of their team. To this end, an objective setting and strategy exercise can help the person move toward higher satisfaction. We would recommend that the employee set short, intermediate and long term objectives for themselves and, where possible, their team. These objectives should meet five SMART criteria.

- Specific

- Measurable

- Attainable

- Relevant

- Time Bound

Once we have SMART objectives in mind, the next step would be to create a task list which would take us step-by-step to the accomplishment of each objective. The key to reaching our objective is to stick to the plan while measuring its effectiveness. These measurements of effectiveness are critical to determining if we are on the right track. If the measurements are in-line, we should continue on course until the objective is met. If the measurements show that we are somehow failing, we need to either tweak the task list, or reassess the objective.

We find that those who focus on individual and team objectives, with a sound strategy for attaining and measuring, have greater satisfaction and better performance than those who simply go to work every day, counting the days until the next paycheck. In the end, organizational effectiveness is impacted by both organizational mission and employee performance. Not all of us have control or even influence over mission, but we all have considerable impact on our own performance and the objectives that we set can help improve that performance and ultimately our satisfaction.

Deal with Employee Failure -- the SAFE Way

Have you ever worked for someone who seems to notice every small error you make (and points it out), but almost never says anything when you are successful? We call this leadership style “The Persecutor” and we see it a lot in both industry and parenting. We have learned by talking with Persecutors that they are trying to motivate people to improve by holding them accountable for their results, but the exact opposite actually occurs because of the way they do it. Employees become demotivated because there is no balance between positive and negative feedback, and because they feel disrespected in the process. People need both correction (what we call “Redirection") for failure and positive feedback for success. So how can you avoid persecution and create the results that you need? We suggest that you use the following redirection guidelines when correcting performance.

- Remain calm. Emotions such as frustration and anger only make us less effective in thinking and communicating. Most of the time those emotions are the result of a “guess” about why the person failed. Avoid guesses and you will have much more control over your emotions.

- Conduct the session in private. One of your primary objectives is to reduce defensiveness so that you can get the employee to help you examine the reason(s) behind the failure and develop a “fix” for the future. Calling someone out in public almost always leads to defensiveness, so make every effort to find a private location for this discussion.

- Eliminate interruptions and distractions. Gaining the full attention of the employee is critical for an effective conversation. Make sure that you control as many distractions as possible and you will get much better attention from your employee.

- Point out positive aspects of performance first, followed by identification of the inadequate performance. Typically the employee will have had some success that you want to continue in the future. Positive feedback helps to strengthen those behaviors, so take this opportunity to create repeated success with positive feedback. Then point out the specific result, action, lack of action, etc. that you have identified as failure. Avoid ambiguous terms such as bad attitude, unmotivated, etc.

- Follow the SAFE* approach to giving feedback.

- Step Up: When you see failure, say something, but say it with respect. If you don’t step up, then the things that have led to this failure will continue to create failure in the future and if you say it the wrong way (disrespectfully) you will create defensiveness and less desire for improvement going forward.

- Ask: Learn the real reason for the failure. Was it motivation, ability, pressure, lack of support, etc? Evaluate the total context that led to the failure before you come up with a plan for improvement.

- Find a Fix: Find a fix for the real reason for the failure. Work with the employee to determine a way to create success in the future. Don’t create the plan yourself, but rather create it in concert with the employee when possible. This brings more ownership and more motivation for improvement.

- Ensure the Fix: Keep an eye on improvement and give feedback accordingly. If the “fix” works and you observe success, then give positive feedback to strengthen performance. If you observe failure, then work your way through the SAFE approach again until you find the real reason for failure and the right fix going forward.

Incentives as a Motivational Tool

Many organizations use both monetary and non-monetary incentives to increase performance. What do good incentive programs look like and are they really useful? First of all, when we talk about incentives, we are talking about the application of something desired by the employee that increases the likelihood that they will perform at a higher level. The objective is to motivate the employee to perform a task/skill for which they are already competent at a faster, more frequent or more reliable level than they have been doing. Incentives, as defined here are not used to teach, but rather to motivate behavior. Good incentive programs have three primary characteristics that lead to success. 1. The behavior required for success is clearly understood. People can only be expected to achieve a result in a particular manner if they understand the standard against which they are being measured. I remember once I told my then 10-year old son to “clean up his mess” after a group of his friends had been at our house for a party. When I came back to evaluate his work, I couldn’t see anything different than before. When I questioned him about his “failure”, he said he did “clean up his mess”; all that other mess was made by his friends. I obviously had not defined the standard against which I was measuring his performance.

2. The measure of success is quantifiable and achievable. The result must be quantitative so that it can be precisely measured. Qualitative measures (e.g. high quality) are too ambiguous and leave room for differences of opinion. Leaving no soda cans or chip bags in the family room after you have cleaned up your mess would have allowed me to have a defendable measure of my sons success in the cleaning task.

3. The incentive is something that is desired by the employees and is clearly tied to success. The incentive that is applied should be something that is seen as worth the effort by employees (or children, as the case may be). If it is not, then it will not serve as a motivator and cannot be expected to improve results. Money is not always required as an incentive. In the example with my son, I told him that as soon as he met our agreed upon standard he could go outside and play basketball with his friends. That non-monetary incentive increased the quantity of items that he picked up and the speed at which he did it. Make sure that you have accurately determined the desirousness of your incentives.

4 Meaningful Ways to Give Positive Feedback

Positive feedback strengthens performance and increases the likelihood of repeated success. Really effective supervisors use more positive feedback than they do negative feedback. Here are four ways to use positive feedback successfully.

1. Give positive feedback in front of peers, but make sure that it is done in a manner that is not embarrassing to the person.

2. Explain “why” you are pleased with their performance. Make sure the person understands the relationship between their performance and the success of the team when possible.

3. Place a “letter of commendation” in the person’s personnel file and make sure that the individual has a copy of the letter.

4. Note their successes as part of their performance review so that the person can see the connection between specific successes and your evaluation of overall performance.

Help!! I'm tired of doing everything myself!

3 Steps to Make Delegating Less Risky Many of us find that we just can’t seem to get done in a day everything that needs to get done. If we work alone, then this may be primarily a personal time management issue, but if we supervise a team, then it may well be a delegation and training issue.

Sometimes we fail to delegate tasks to our team members because we simply don’t trust them. We have delegated to someone in the past and they have failed us, so now we are afraid to try it again. The fact is that, as supervisors, our job is to get results through the efforts of our team members and if we aren’t delegating, we are not doing what we are getting paid to do.

So how do you develop enough trust so that you are willing to take the “risk” of delegating?

1. Do an Ability Inventory -- The first step is to accurately understand the ability level of each team member with respect to each task for which they have responsibility. An honest evaluation of ability will give you a starting point.

2. Delegate with Support -- Once you have this information, then you can determine what and to whom you can give more responsibility. Make sure that you provide enough support to ensure success without “looking over their shoulder” all the time.

3. Develop “The Bench” -- Additionally, you need to determine an on-the-job training process to develop the skills needed by each team member so that they can be successful when delegated specific tasks. This gives you more “bench strength” so that you have more options for delegation.

Balancing delegation and training will really help you manage your time and also help manage the time of your team members.