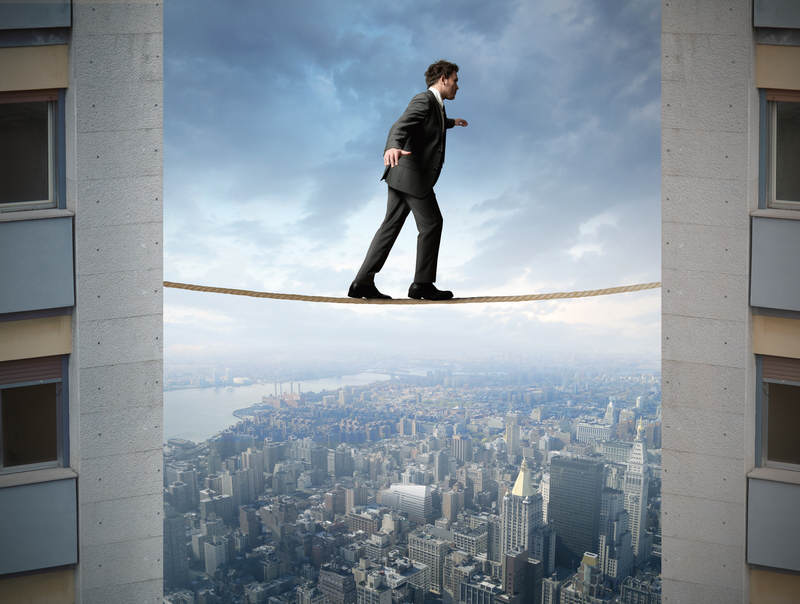

In the world of safety, culture is a big deal. In one way or another, culture helps to shape nearly everything that happens within an organization - from shortcuts taken by shift workers to budget cuts made by managers. As important as it is, though, it seems equally as confusing and intractable. Culture appears to emerge as an unexpected by-product of organizational minutia: A brief comment made by a manager, misunderstood by direct-reports, propagated during water cooler conversations, and compounded with otherwise unrelated management decisions to downsize, outsource, reassign, promote, terminate…

Safety culture can either grow wild and unmanaged - unpredictably influencing employee performance and elevating risk - or it can be understood and deliberately shaped to ensure that employees uphold the organization’s safety values.

Pin it Down

The trick is to pin it down. A conveniently simple way of capturing the idea of culture is to say that it is the “taken-for-granted way of doing things around here;” but even this is not enough. If we can understand the mechanics that drive culture, we will be better positioned to shift it in support of safety. The good news is that, while presenting itself as extraordinarily complicated, culture is remarkably ordinary at its core. It is just the collective result of our brains doing what they always do.

Our Brains at Work

Recall the first time that you drove a car. While you might have found it exhilarating, it was also stressful and exhausting. Recall how unfamiliar everything felt and how fast everything seemed to move around you. Coming to a four-way stop for the first time, your mind was racing to figure out when and how hard to press the brake pedal, where the front of the car should stop relative to the stop sign, how long you should wait before accelerating, which cars at the intersection had the right-of-way, etc. While we might make mistakes in situations like this, we should not overlook just how amazing it is that our brains can take in such a vast amount of unfamiliar information and, in a near flash, come up with an appropriate course of action. We can give credit to the brain’s “executive system” for this.

Executive or Automatic?

But this is not all that our brains do. Because the executive system has its limitations - it can only handle a small number of challenges at a time, and appears to consume an inordinate amount of our body’s energy in doing so - we would be in bad shape if we had to go through the same elaborate and stressful mental process for the rest of our lives while driving. Fortunately, our brains also “automate” the efforts that work for us. Now, when you approach a four-way-stop, your brain is free to continue thinking about what you need to pick up from the store before going home. When we come up with a way of doing something that works - even elaborate processes - our brains hand it over to an “automatic system.” This automatic system drives our future actions and decisions when we find ourselves in similar circumstances, without pestering the executive system to come up with an appropriate course of action.

Why it Matters

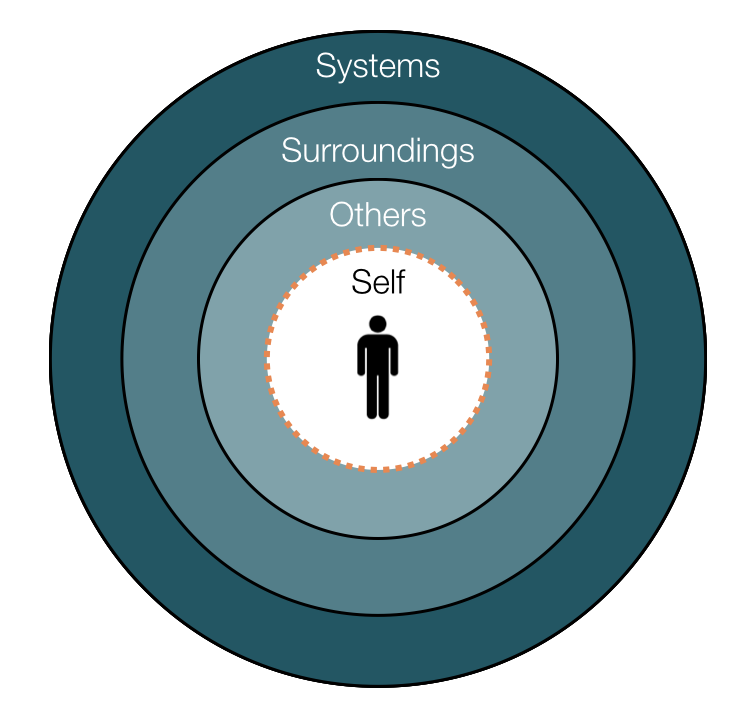

What does driving have to do with culture? Whatever context we find ourselves in - whether it is a four-way-stop or a pre-job planning meeting - our brains take in the range of relevant information, come up with an effective course of action, try it out and, when it works, automate it as “the way to do things in this situation.”

For Example

Let’s imagine that a young employee leaves new-hire orientation with a clear understanding of the organization’s safety policies and operating procedures. At that moment, assuming that he wants to succeed within the organization, he believes that proactively contributing during a pre-job planning meeting will lead to recognition and professional success.

Unfortunately, at many companies, the actual ‘production’ context is quite different than the ‘new-hire orientation’ context. There are hurried supervisors, disinterested ‘old timers’, impending deadlines and too little time, and what seemed like the right course of action during orientation now looks like a sure-fire way to get ostracized and opposed. His brain’s “executive system” quickly determines that staying quiet and “pencil whipping” the pre-job planning form like everyone else is a better course of action; and in no time, our hapless new hire is doing so automatically - without thinking twice about whether it is the right thing to do.

Changing Culture

If culture is the collective result of brains figuring out how to thrive in a given context, then changing culture comes down to changing context - changing the “rules for success.” If you learned to drive in the United States but find yourself at an intersection in England, your automated way of driving will likely get you into an accident. When the context changes, the executive system has to wake up, find a new way to succeed given the details of the new context, and then automate that for the future.

How does this translate to changing a safety culture? It means that, to change safety culture, we need to change the context that employees work in so that working safely and prioritizing safety when making decisions leads to success.

Three Basic Steps:

Step 1

Identify the “taken-for-granted” behaviors that you want employees to adopt. Do you want employees to report all incidents and near-misses? Do you want managers to approve budget for safety-critical expenditures?

This exercise amounts to defining your safety culture. Avoid the common mistake of falling back on vague, safety-oriented value statements. If you aren’t specific here, you will not have a solid foundation for the next two steps.

Step 2

Analyze employees’ contexts to see what is currently inhibiting or competing against these targeted, taken-for-granted behaviors. Are shift workers criticized or blamed by their supervisors for near-misses? Are the managers who cut cost by cutting corners also the ones being promoted?

Be sure to look at the entire context. Often times, factors like physical layout, reporting structure or incentive programs play a critical role in inhibiting these desired, taken-for-granted behaviors.

Step 3

Change the context so that, when employees exhibit the desired behaviors that you identified in Step 1, they are more likely to thrive within the organization.

“Thriving” means that employees receive recognition, satisfy the expectations of their superiors, avoid resistance and alienation, achieve their professional goals, and avoid conflicting demands for their time and energy, among other things.

Give It a Try

Shifting culture comes down to strategically changing the context that people find themselves in. Give it a try and you might find that it is easier than you expected. You might even consider trying it at home. Start at Step 1; pick one simple "taken-for-granted" behavior and see if you can get people to automate this behavior by changing their context. If you continue the experiment and create a stable working context that consistently encourages safe performance, working safely will eventually become "how people do things around here."