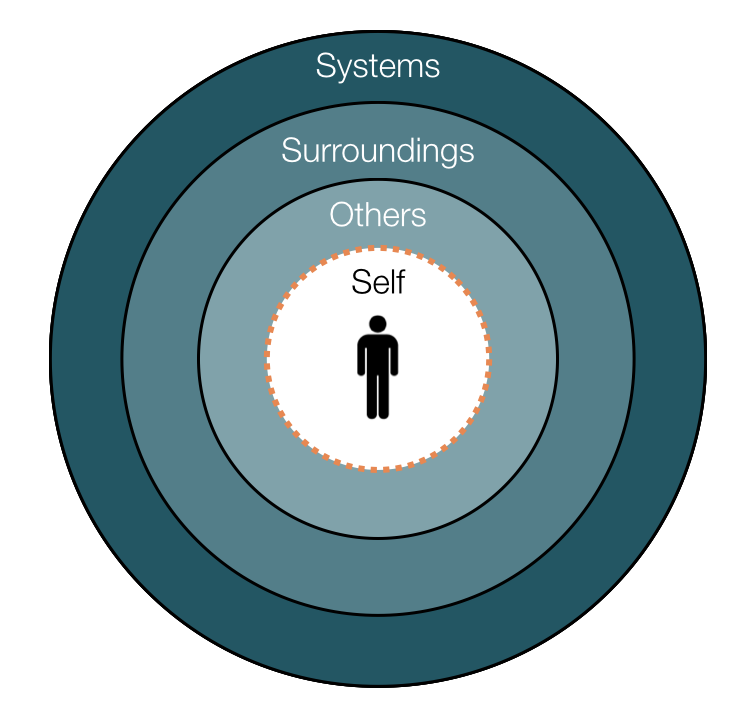

We live and work in environments that are continuously increasing in complexity, which puts an even greater strain on our ability to make quick, accurate decisions. (See Human Error and Complexity: Why your safety “world view” matters). Among the many important considerations for organizational leaders is how age affects people’s decisions and performance in these complex environments. Though the cognitive and socio-emotional skills of younger workers (under 25 years of age) are still developing (see Protecting Young Workers from Themselves), this group is at its peak performance with respect to speed of information processing and physical abilities…including vision, hearing, strength, flexibility and reaction time.

On the other hand, the opposite is generally true of the 55+ age group, even though there are individual differences. Aging tends to bring with it a decline in just about all of these physical abilities as well as some cognitive abilities. (Note that we are talking about “normal” aging, absent significant pathology such as Alzheimers and Dementia.)

While research has demonstrated that aging has little or no effect on general intelligence, it can impact other aspects of cognition. The aging brain is slower to shift attention to new stimuli in the environment and also slower to recall uncued relevant information. Additionally, short term (“working”) memory functions less efficiently with age. While an older worker might make fewer mistakes in decision making, he or she will normally require more time to make those decisions. So when a task is complex and requires the manipulation of information or ignoring irrelevant information, there may be age related decline in performance (e.g., Balota, et al, 2000), especially when the older person is under pressure to perform. In short…

Complexity + Time Pressure = Kryptonite for the Aging Brain

Left at that, it would be bad news for the aging worker in our increasingly complex and fast-paced world. HOWEVER, as with nearly everything in life, there are more pieces to this puzzle. Two of these pieces are experience and contextual cues. Research has shown that older adults tend to perform well on recognition tasks where contextual cues are present. This could help explain their lower incident rate relative to younger workers, since older adults recognize and process contextual cues effectively because of their past experience. They are more likely to recognize a hazard as a hazard because they have experienced it in the past. In short…

Contextual Cues + Experience = The Great Equalizer

Adolescents and young adults don’t have the experience with contextual cues that older adults do, so they are less likely to recognize them and respond to them. Younger workers’ higher speed of processing is offset by their lack of experience with contextual cues…and vice versa with older workers. These findings provide additional support for the need to have older and younger workers learn to work together so as to capitalize on their age-related strengths. In short…

Older Workers + Younger Workers = Better Decisions

Unfortunately, there are common and misguided stereotypes about both younger and older workers, which can keep us from honestly exploring the many ways that they may contribute to organizational success. Understanding the truth about the developing brain of younger workers and the aging brain of older workers may just be a key to thriving in our increasingly complex world.