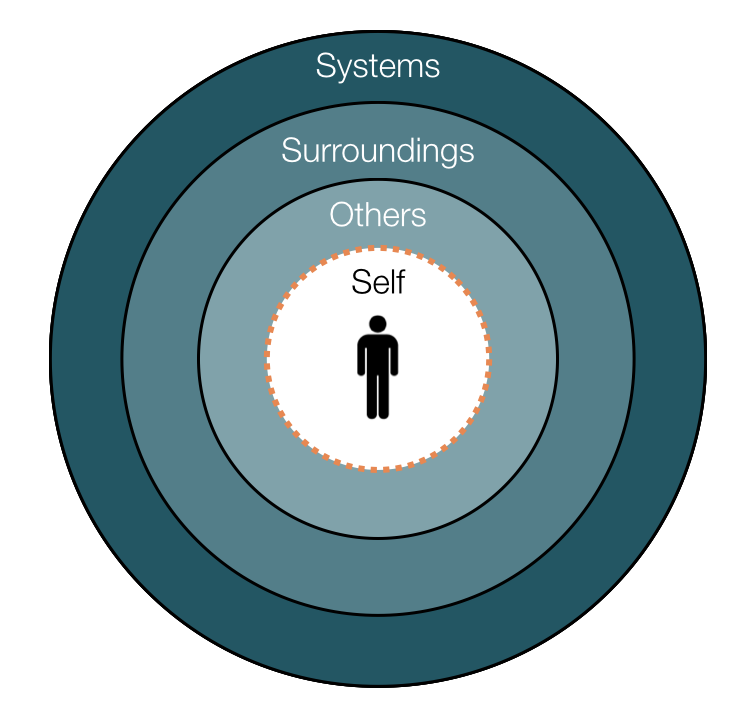

Research and personal experience both demonstrate that people are less likely to intervene (offer help) when there are other people around than they are when they are the only person observing the incident. This phenomenon has come to be known as the Bystander Effect and understanding it is crucial to increasing intervention into unsafe actions in the workplace. It came to light following an incident on March 13, 1964 when a young woman named Kitty Genovese was attacked by a knife-wielding rapist outside of her apartment complex in Queens, New York. Many people watched and listened from their windows for the 35 minutes that she attempted to escape while screaming that he was trying to kill her. No one called the police or attempted to help. As a matter of fact, her attacker left her on two occasions only to return and continue the attack. Intervention during either of those intervals might have saved her life. The incident made national news and it seemed that all of the “experts” felt that it was "heartless indifference" on the part of the onlookers that was the reason no one came to assist her. Following this, two social psychologists, John Darley and Bibb Latane began conducting research into why people failed to intervene. Their research became the foundation for understanding the bystander effect and in 1970 they proposed a five step model of helping where failure at any of the steps could create failure to intervene (Latane & Darley, 1970).

• Step 1: Notice That Something Is Happening. Latane & Darley (1968) conducted an experiment where male college students were placed in a room either alone or with two strangers. They introduced smoke into the room through a wall vent and measured how long it took for the participants to notice the smoke. What they found was that students who were alone noticed the smoke almost immediately (within 5 seconds) but those not alone took four times as long (20 seconds) to notice the smoke. Just being with others, like working in teams in the workplace can increase the amount of time that it takes to notice danger.

• Step 2: Interpret Meaning of Event. This involves understanding what is a risk and what isn’t. Even if you notice that something is happening (e.g., a person not wearing PPE), you still have to determine that this is creating a risk. Obviously knowledge of risk factors is important but when you are with others and no one else is saying anything you might think that they know something that you don’t about the riskiness of the situation. Actually they may be thinking the same thing (pluralistic ignorance) and so no one says anything. Everyone just assumes that nothing is wrong.

• Step 3: Take Responsibility for Providing Help. In another study, Darley and Latane (1968) demonstrated what is called diffusion of responsibility. What they demonstrated is that as more people are added the less responsibility each assumes and therefore the less likely any one person is to intervene. When the person is the only one observing the event then they have 100% of the responsibility, with two people each has 50% and so forth.

• Step 4: Know How to Help. When people feel competent to intervene they are much more likely to do so than when they don’t feel competent. Competence engenders confidence. Cramer et al. (1988) demonstrated that nurses were significantly more likely to intervene in a medical emergency than were non medically trained participants. Our research (Ragain, et al, 2011) also demonstrated that participants reported being reluctant to intervene when observing unsafe actions because they feared that the other person would become defensive and they would not be able to deal with that defensiveness. In other words, they didn’t feel competent when intervening to do so successfully, so they didn’t intervene.

• Step 5: Provide Help. Obviously failure at any of the previous four steps will prevent step 5 from occurring, but even if the person notices that something is happening, interprets it correctly, takes responsibility for providing help and knows how to do so successfully, they may still fail to act, especially when in groups. Why? People don’t like to look foolish in front of others (audience inhibition) and may decide not to act when there is a chance of failure. A person may also fail to act when they think the potential costs are too high. Have you ever known someone (perhaps yourself) who decided not to tell the boss that he is not wearing proper PPE for fear of losing his job?

The bottom line is that we are much less likely to intervene when in groups for a variety of reasons. The key to overcoming the Bystander effect is two fold, 1) awareness and 2) competency. 1) Just knowing about the Bystander effect and how we can all fall victim to this phenomenon makes us less likely to do so. We are wired to be by-standers, but just knowing about this makes us less likely to do so. 2) Training our employees in risk awareness and intervention skills makes them more likely to identify risks and actually intervene when they do recognize them.